|

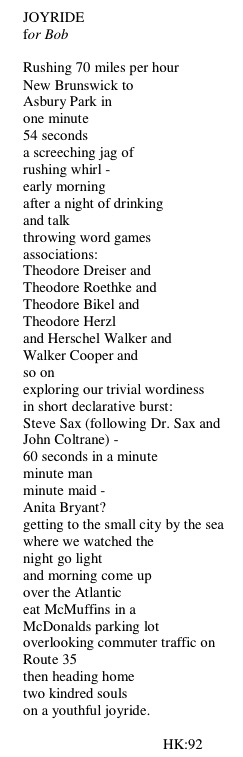

| The cover of my first attempt at a literary zine, named for the Kerouac novel. |

I thought I was a beat, but I was just a boy

Notes on Re-Reading Kerouac in my 50sPart 12

(Read Part 11 here, Part 10 here, Part 9 here, Part 8 here, Part 7 here, Part 6 here, Part 5 here, Part 4 here, Part 3 here, Part 2 here and Part 1 here.)

When I was 19, On the Road was a revelation. Like so many boys my age, I was looking for a different kind of validation than the one I’d received from families and teachers, a way to escape the expectations and, at least figuratively, find a new road.

On the Road provided me a figurative road map, a permission slip, a glimpse into a committed sense of rebellion. Sal and company may have had difficulty committing to relationships, but they were committed to chasing pleasure, to seeking knowledge, to living beyond the confines of what was becoming a staid and stultifying post-war landscape.

As the events of the novel unfold, the nation is emerging from the massive military build-up of World War II. The Depression was still present in the minds of Americans, with enough people remaining left out of FDR’s New Deal and the war’s injection of Keynesian spending into the economy. The nation was on the cusp of change.

On the Road offers evidence of an America slowly receding — hobos riding the rails, a vast migrant economy that was best portrayed in the 1930s by John Steinbeck, still extant farm areas incorporated into medium and large-sized cities. The America of On the Road was already in the rear view mirror when the book was published in 1957. The GI Bill was giving the white working class a way out of the factories. Suburbanization led to white flight from the cities, even as the Great Migration was bringing more blacks to northern cities. The economy was becoming nationalized — not in a Soviet manner, but through the growth of national retail chains and large corporations, which created a need for a new class or at least a larger class of middle managers.

I admit that my short overview of the era is, in many ways, a caricature of the time. I’m distilling a historical period to its broad outlines. But these broad outlines are important, because they define the context into which the novel was born, helping to define for us what On the Road meant to younger readers when it came out. On the Road was both a harbinger of a new cultural order and an effort to preserve something of America’s mythic past.

Sal’s rebellion borrows from an American mythology, and On the Road shares DNA with other classics — Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and several of his short stories, Fitzgerald, Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Thoreau’s Walden: A Life in the Woods, Dreiser — in its central themes and reliance on several key American myths: that America is an unending continent; that we all can remake ourselves, can discard our identities; that we can make new starts by taking to the road; and that, by going back to the soil or he wilderness, we can find something more authentic.

All of these are present in On the Road in different ways and make the book very much a link in the chain of American literature and part of the vast conversation writers have with the past and future.

And it shares DNA with J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, as well, which was written at the same time as Kerouac was first working on On the Road but published six years before Kerouac’s novel made its debut. Both are direct attacks on the mainstream. Catcher in the Rye‘s Holden Caulfield is younger and decidedly upperclass, but his rebellion is aimed at the same basic targets: an establishment that he views as enforcing a conformity that is suffocating. Holden runs away after failing out of boarding school, his refusal to go home serving as a statement of purpose and a rebellion without a clear argument; Sal takes to the road, running deeper into a mythic America, chasing authenticity at a time when advertising was rising to art form and the company man (or the man in the grey flannel suit) was the standard.

Kerouac’s writing stood against it — and, in many ways, still does. That it became the model from which both the early hipster and the hippie would grow is not his fault, or not completely. He hated that his readers often missed the sadness in the book, and the painful, grinding reluctance that marks his Big Sur — a book that chronicles his reaction to fame, his efforts to find some piece, and his total descent into alcoholic madness.

Kerouac’s late years are marked by contradictions and a debilitating descent into drink. His underlying political conservatism had always been there. Burroughs describes him in Jack’s Book, the Gifford/Lee biography, as an “Eisenhower man” who “believed in the old-fashioned virtues, in America, and that Europeans were decadent, and he was violently opposed to communism and any sort of leftist ideologies” (Gifford 303). And he railed against the new anti war protesters, not because supported the violence in Vietnam, but because they were not showing sufficient respect for the country he loved.

But Kerouac’s On the Road — along with The Dharma Bums and The Subterraneans — also served as a template for this new generation. These were Kerouac’s kids, in a literary sense, taking to the road, seeking kicks, doing what they could to slip the grip of ’50s conformity and to dull the knowledge that we were living under the existential threat on nuclear annihilation.

The context, again, is significant. Norman Mailer, in his essay “The White Negro,” attributes the hipster urge typified by the Beats to a sense of doom, a fear of impending atomic calamity. He likens it to the fatalism of an African American population that lived everyday under existential threat, i.e., the purposeful and arbitrary violence of the Jim Crow South and equally racist North. Both the hipster — whom he dubs the “white negro” — and the African American seek pleasure as a way of fending off the doom. The difference, he says, is that African Americans were also responding to fatalism with political engagement; the hipster was not.

It’s a simplistic analysis that idealizes black Americans as a type, but it does offer an explanation as to what might be underlying this revolt, one that ties into the philosophical debates of pre-war and post-war Europe. Existential dread does appear to trigger some of the hedonism of the Beats — Ginsberg’s poems “Howl,” “America” and “A Supermarket in California” are thick with it, as is the work of Gregory Corso and the madness of Burroughs’ novels.

The baby-boom generation grows up in the shadow of the bomb — I can remember air-raid drills at my New York elementary school in the late-1960s — and with a sense of unending prosperity that creates a new sense of boredom. Dean is key to this analysis, I think. He is about 20 when On the Road begins. Sal was about five years older. They are, in so many ways, still kids, as is the rest of their crowd. Theirs is partly a youthful, hedonistic rebellion that grows from the natural need of the not-quite-adult to make his own way, while also fighting a sense of ennui that hangs over this first generations of teens to not be forced into the workforce.

Rebel Without a Cause — along with a number of scare films about juvenile delinquency, a genre that has had a long history — offers a glimpse into this: knife fights and games of chicken, a sense of teen invincibility crossed with a sort of desperation for belonging and control. It’s not just the James Dean character, Jim Stark, but the entire youth subculture in the film that seems to be struggling for some kind of purpose, for an existence of its own.

Sal Paradise faces the same struggle, fighting a deep ennui as On the Road opens. Sal has just gone through a break up and a “serious illness that I won’t bother to talk about, except that it had something to do with the miserably weary split-up and my feeling that everything was dead” (3). It’s an often overlooked element of the novel, which too often is portrayed solely as a precursor to the buddy-film genre, or as a joyful expression of new identity. The book, while tilting at expansiveness, is really about limits — the limits that exist in relationships, the limits of a continent, the inability, ultimately to escape one’s self.

And yet, rebellion and motion are the underlying motifs, the foundation on which failures of its characters lie and from which its language draws its energy. When I first read the book, what drew me in was the language — which has an odd sense of swing and can have the feeling that it is rushing forward, while slowing to a crawl as Sal becomes contemplative.

“In no time at all,” he writes as Dean guns a massive Cadillac limousine toward Chicago and the book’s decisive events,

we were back on the main highway and that night I saw the entire state of Nebraska unroll before my eyes. A hundred and ten miles an hour straight through, an arrow Road, sleeping towns, no traffic, and the Union Pacific streamlined falling behind us in the moonlight. I wasn’t frightened at all that night; it was perfectly legitimate to go 110 and talk and have all the Nebraska towns — Ogallala, Gothenburg, Kearney, Grand Island, Columbus — unreal with dreamlike rapidity as we roared ahead and talked. (228)

The speed, the way the towns exist in name only, as highway signs, the night, the talking — this is the romance of the novel, it’s magnetic allure. I remember drinking tequila and smoking dope one night with my pal Bob in the house we rented. It was a night of big conversation, as every night was. We were 20, unformed, gazing ahead, and sometime deep in the night we decided to head to Asbury Park, racing east on the highway, doing 70, 80, arriving in the decaying Shore town made famous by my idol, Bruce Springsteen, hitting a McDonald’s for breakfast, realizing we had no cash, fleeing without our food, and racing home in the same burst of energy and youthful exuberance that had us up all night in the first place. This is what 20-year-olds do — or did, or maybe it was just us. We lived that way, alternating between the frenzy, partying at night, and the doldrums (to borrow a word from Ginsberg), working boring day jobs and doing the things you need to do to survive. And we read and wrote and played our music loudly, and “tried to walk like the heroes we thought we had to be” (Springsteen, “Backstreets”).

If you need your ex-girlfriend or ex-boyfriend to come crawling back to you on their knees (even if they're dating somebody else now) you must watch this videoright away…(VIDEO) Get your ex back with TEXT messages?

Did you know you can shorten your urls with AdFly and make money from every visit to your short urls.

Anyone here wants a FREE MC DONALD'S GIFT CARD?